LPDC simulation of alloy wheel to predict the defects produced due to improper die heating.

Introduction

Alloy wheels were first developed in the last sixties to meet the demand of race track enthusiasts who were constantly looking for an edge in performance and styling. It was an unorganized industry then. Since its adoption by OEM’s, the alloy wheel market has been steadily growing. Today, thanks to a more sophisticated and environmentally conscious consumer, the use of alloy wheels has become increasingly relevant. With this Increased demand came new developments in design, technology and manufacturing processes to produce a superior with a wide variety of designs.

The aluminum alloy automotive wheel industry is very competitive and manufacturers are constantly under pressure to improve quality and reduce cost. These factors drive manufacturers to increase production rates while attempting to also maintain, or preferably reduce, scrap rates.

Production rates may be increased by reducing the time required to produce each part. Aluminum alloy wheels are generally produced using two variants of the low pressure die casting (LPDC) technique: the conventional air-cooled version, which uses compressed air as the cooling media, and the water-cooled version, which uses water as the cooling media. The water-cooled LPDC process offers enhanced cooling and solidification rates, thus reducing the time required to produce a wheel. Higher cooling rates also provide the added benefit of finer microstructure, which in turn leads to superior fatigue performance. However, being a relatively new technique, the water-cooled LPDC technique still faces challenges from higher operational costs and higher scrap rates.

The defects that can lead to scrap that are commonly found in aluminum alloy wheels include porosity, oxide films, and exogenous inclusions. Oxide films and exogenous inclusions can be effectively eliminated by inducing quiescent die filling and using filters. Porosity is however very difficult to control and completely remove. Porosity impacts both the mechanical performance and cosmetic appearance, and is a prominent defect of concern. The formation and growth of porosity can be traced back to the casting process, and the severity can be significantly reduced via the proper design and operation of die cooling systems.

Historically, the design of the die, including the cooling systems and the associated operational parameters, were arrived at through a combination of experience and trial-and-error optimization. This design methodology typically involves long lead times, and multiple stages of prototyping / preproduction trials before the die is qualified for full production. Depending on the success of this approach, initial production runs can result in high scrap rates and less than optimum production rates. Mathematical modeling offers the ability to enhance design decisions with quantitative information and to reduce development times by replacing plant trials with simulations run in a computer. In recent years, there has been an increased usage of numerical optimization techniques for engineering design problems. Numerical optimization provides a systematized and versatile procedure for arriving at a design solution. It can reduce the time required to generate production-ready designs, removes experiential biases from the design process, and virtually always yields some design improvement. Though the benefits are obvious, relatively little effort has been devoted to applying numerical optimization technique to casting processes in general, not to mention the wheel casting process. Currently, the wheel manufacturing industry is still relying on time-consuming and expensive trial-and-error, in–plant trials. Against this background, this study aims to develop an optimization methodology that improves the quality and productivity of the LPDC wheel casting process.

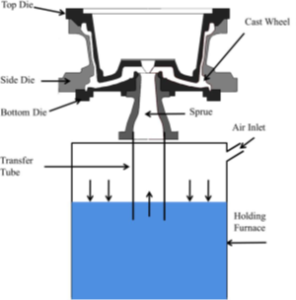

Low Pressure Die Casting Process

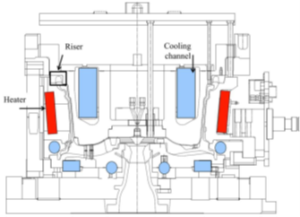

The LPDC technique is generally used in the production of rotationally symmetric parts. It can produce large volumes of high-quality, near-net-shape aluminum components. As shown in below figure a typical LPDC casting machine is comprised of a die assembly sitting above an electrically heated furnace, which contains a reservoir of liquid metal (shown in blue). For wheel production, the die assembly typically contains one top die, two side dies and one bottom die. The LPDC process is cyclic where each cycle starts with the pressurization of the holding furnace. The melt is pushed up into the die cavity via the transfer tube and sprue. The melt is then cooled and solidified by heat transfer from the melt to the die and then from the die to the cooling systems and/or to the surrounding air by convection and radiation. After solidification is complete, the side dies open and the top die is raised vertically. The wheel moves up with the top die before being ejected onto a tray, and the die closes for the next cycle.

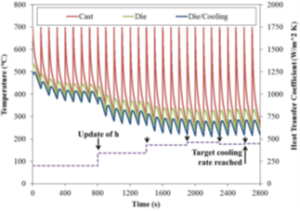

At the start of an LPDC casting campaign, the die is preheated either off-line in an oven or in the casting machine via torches. Once casting starts, the die temperature distribution evolves considerably from cycle-to-cycle, as the die moves toward cyclic steady state (cyclic steady state is reached when the die temperature distribution at the end of the cycle is equal to the die temperature at the beginning of the cycle). The wheels cast from these first cycles generally contain significant defects and are thus discarded. Depending on the mass of the die and the cooling conditions, the die will take 5 – 10 casting cycles to approach cyclic steady. Optimal operation / productivity of an LPDC process occurs when the process reaches cyclic steady-state quickly and maintains stable operation throughout the casting campaign.

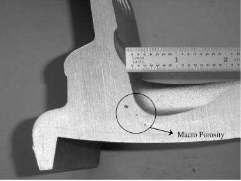

The optimal cooling conditions may be defined as those that lead to directional solidification in the wheel while achieving short cycle time (high cooling rates). As illustrated in above figure, directional solidification in a wheel refers to solidification starting at the inboard-rim flange, progressing down through the rim, across the spokes, and ending just below the hub in the top of the sprue. If this directional solidification pattern is not achieved, shrinkage porosity will form. Shrinkage porosity forms when liquid metal fails to feed regions of a casting to offset the volumetric contraction that occurs during the liquid to solid transformation. This typically occurs when a region of liquid metal is isolated or encapsulated by solid metal. In wheel castings, shrinkage porosity is commonly found at the hub-spoke junction and the spoke-rim junction. where there is large thermal mass and a transition in the solidification front geometry. The combination of these two phenomena can result in these areas becoming hot spots where local solidification is delayed. The delay in solidification results in a loss of connection to the liquid supply leading to void formation. Figure shows an example of shrinkage porosity in the spoke-rim junction. Cooling rates are also important in determining the quality of the wheel.

Photograph of sectioned wheel showing the presence of macro-porosity in the spoke-rim junction

Casting Simulation

Case-1 Alloys Wheel Casting without Die Temperature and Cooling

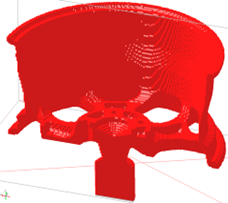

Figure below shows the cad view alloy wheel casting with gating system for LPDC process.

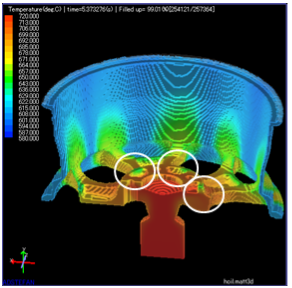

Below shows the temperature distribution during filling of molten metal into cavity, highlighted regions are temperature drop in casting

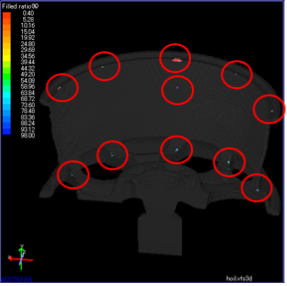

Below figure shows the solidification Pattern (Progressive and Directional solidification) during solidification stage, highlighted regions are isolated from the directional solidification in alloy wheel and raiser it will not feed further and finally it will prone to shrinkage porosity defect.

Below figure shows the degree of soundness in casting. highlighted regions prone to shrinkage porosity defect.

Die Thermal Balancing with Cooling & Heating line

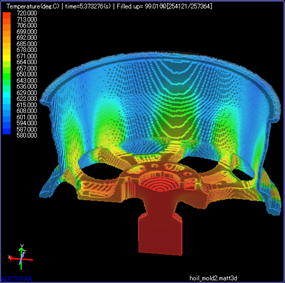

As mentioned in the previous section, there are two routes to remove the heat that enters the die from the liquid metal. The first is by heat transfer to cooling media (air or water) flowing in channels within the die and the other is by convective and radiative heat transfer to the environment surrounding the die. Between the two, the cooling system (cooling media in the channels) is responsible for removing the majority of the heat. An example of an LPDC wheel die, configured for water cooling, is shown in above figure. The die structure is complex, containing multiple cooling channels (shown in blue) and sometimes heaters (shown in red). Water is passed through the cooling channels for predefined periods during each cycle, and at the end of each period, water may be purged from the channels by blowing compressed air through the system. The predefined periods are comprised of a start time and end time within each cycle and are generally different for each channel. In addition, the water flow rate is also typically different for each channel. In combination with differences in channel cross section, the flow rate determines an effective heat transfer rate for each channel when switched on. The combined parameters used for each cooling channel represent a cooling program, which is the key factor in determining the overall effect of cooling on the die and casting.

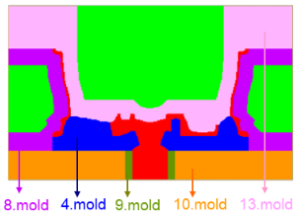

Casting Simulation Considering Die assembly with cooling lines

Case-2 Alloys Wheel Casting with Die Temperature and Cooling

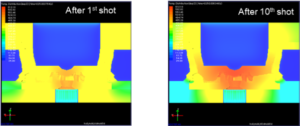

Below figure shows the temperature distribution in die during 1st cycle and 10 cycle.

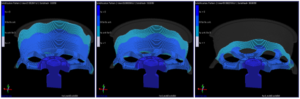

Below figure shows the temperature distribution during filling of molten metal into cavity, temperature distribution in casting. we above the liquidus temperature. less chances of cold shut, unfilling/ misrun defects.

Below figure shows the solidification pattern (Progressive and Directional solidification) during solidification stage, using die temperature and Thermal balancing to get directional solidification in alloy wheel and raiser, it will feed till the end and finally less changes shrinkage porosity defect.

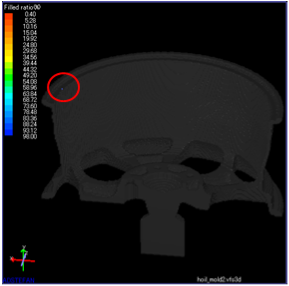

Below figure shows the degree of soundness in casting. highlighted regions prone to shrinkage porosity defect. no shrinkage porosity observed in alloy wheel area.

Conclusion

Authors have used a casting simulation software ADSTEFAN to study the effect of die temperature on casting quality and reduction/elimination of defects. All other process parameters (including gating design and process parameters can be studied together to develop robust sensitivity envelope for casting. Using such analysis, decision on appropriate die temperature and process parameter selections can be made.

Rational judgements can be made about the cost implications of each of the matrix in the sensitivity analysis.

Process design of casting Alloys wheel made out of Aluminum alloy is optimized, considering the plant operational conditions and using casting simulation tool effectively.

Recent Posts

- LPDC simulation of alloy wheel to predict the defects produced due to improper die heating.

- Implementing Machine learning on Defect prediction for Investment casting through ADSTEFAN casting simulation software

- Methods for Indian Casting Manufacturers to Overcome Fluctuating Raw material price

- Casting rejection can be controlled, Here are important tips

- Die Casting 4.0 – Casting Defect Prediction by Machine Learning for Die casting industries using Casting Simulation Software

- Types of Cooling Lines and Thermal balancing die casting Using ADSTEFAN Casting Simulation Software for Casting gating optimisation & Cooling lines optimization

- Yes! We can perform air entrapment prediction and overcome by air entrapment simulation using ADSTEFAN casting simulation software. Here is how we can do

- Are You Facing Challenges in Utilizing Casting Simulation Software? Here’s How to Overcome Them

- Better practice for effective utilization of simulation software

- More Yield, Fewer Defects – How ADSTEFAN helps to Transforms Gating Design! – Case study on Steel Valve body castings